Introduction

This year, during several mantrailing seminars, I received the suggestion that adding a bit of obedience before the trail start could improve my dog’s performance. At first, I was intrigued, how would a simple sit or focus exercise make such a difference? Digging deeper, I discovered fascinating mechanics behind this idea: the way emotions, arousal, and focus interact at the very start of a trail. As someone who has worked in IT for more than 24 years, I couldn’t help but notice the parallels. Many of these principles – finding the right balance between motivation and stress, managing focus, avoiding overload are the same ones I’ve seen play out when leading teams of all sizes. It turns out, what drives success in the workplace for creative thinking isn’t so different from what helps a dog succeed on the trail.

The start in mantrailing is critical

For mantrailing dogs the moments before and at the start of a trail are crucial. Many handlers observe that trail success mostly depends on a good start, since a dog’s initial focus and direction set the tone for the entire search. At the trail start, dogs undergo a surge of emotion and arousal – whether it’s excitement, anxiety, or frustration – which can profoundly influence their motivation and performance. Understanding how these emotional spikes affect a working dog’s ability to trail is key to optimizing training and ensuring consistent success. Handlers of high-drive breeds like Belgian or German Shepherds often report their dogs whining, panting, or trembling with anticipation right before being sent on a trail – clear signs that emotional arousal is ramping up. If not managed, such heightened emotions can either supercharge a dog’s motivation or sabotage its ability to work effectively from the outset.

Optimal arousal vs. over-arousal (the Yerkes-Dodson principle)

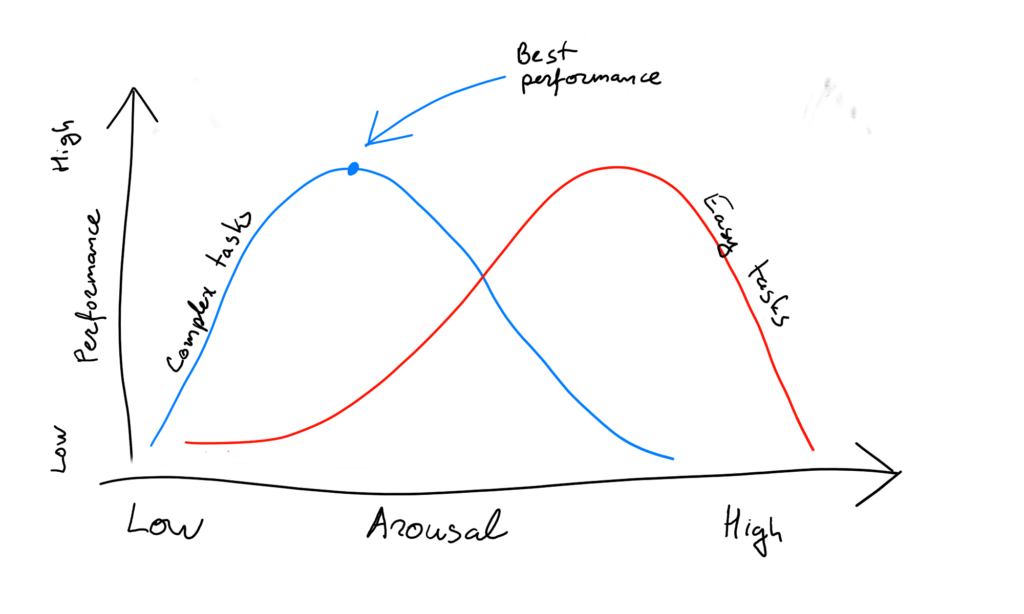

Striking the right balance in a dog’s arousal level is critical. According to the well-established Yerkes-Dodson law (originally from human psychology but applicable to dogs), performance improves as arousal increases, up to an optimal point – beyond which performance deteriorates sharply.

In practical terms, a moderate level of excitement can focus a dog’s energy and sharpen its drive, while excessive excitement tips into stress that hinders concentration. Working dogs thrive in a sweet spot of arousal. At this peak arousal, the dog’s natural drive is fully engaged and its energy is channeled into intense focus – it “is on top of the world” and can trail effectively with ease. If arousal rises past this peak, however, the dog’s performance will start to decrease. Trainers often summarize this as “too low = sluggish, too high = scatterbrained”. It is worth mentioning, that Yerkes-Dodson law defines different optimal arousal levels for easy mechanical tasks (much higher) and complex tasks such as problem solving and creative thinking – in this case optimum arousal is lower for best performance.

One trainer’s story illustrates this balance well: she advised a competitor with a calm Golden Retriever to pump up the dog’s energy before an obedience trial, and indeed the revved-up retriever performed smoothly and accurately in the ring. But when another handler applied the same excitement routine to her already-wired Schnauzer, the over-aroused Schnauzer lost focus and misinterpreted cues – essentially falling off the performance cliff due to being too excited. Scientific testing backs this up: in one study, increasing arousal helped dogs with lower natural excitability perform better, whereas in already excitable dogs it caused a significant deterioration in performance. The researchers concluded that “if you have an easy-going, low-key dog, boosting his excitement before work makes sense, but for a high-strung dog, it’s better to start as calm as possible.” In mantrailing terms, this means tailoring the start-of-trail routine to the individual dog’s temperament. A relatively placid bloodhound or retriever may need a fun game or “intensity start” to get in the zone, while an amped-up Malinois might need a soothing ritual (like a obedience sit or calm harnessing) to avoid tipping into over-arousal.

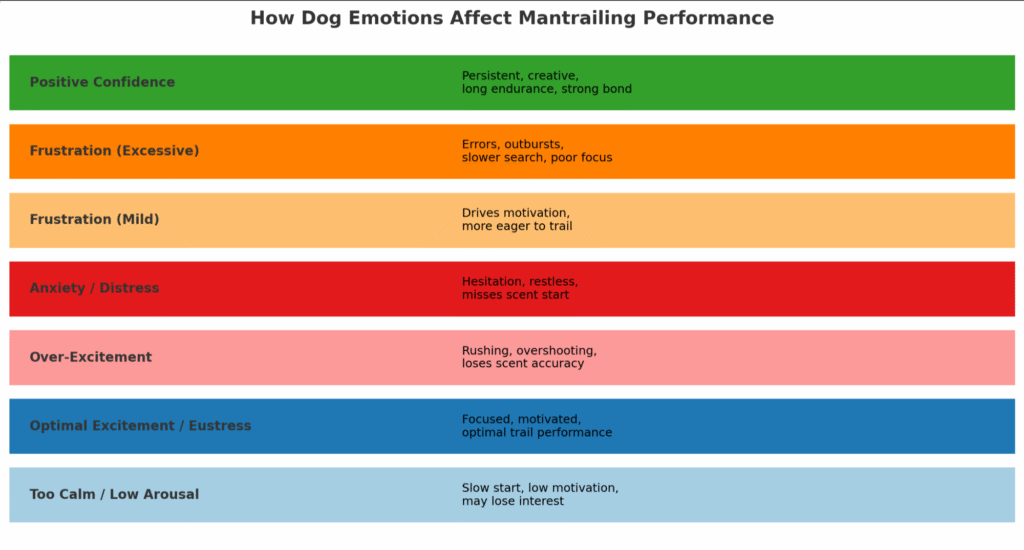

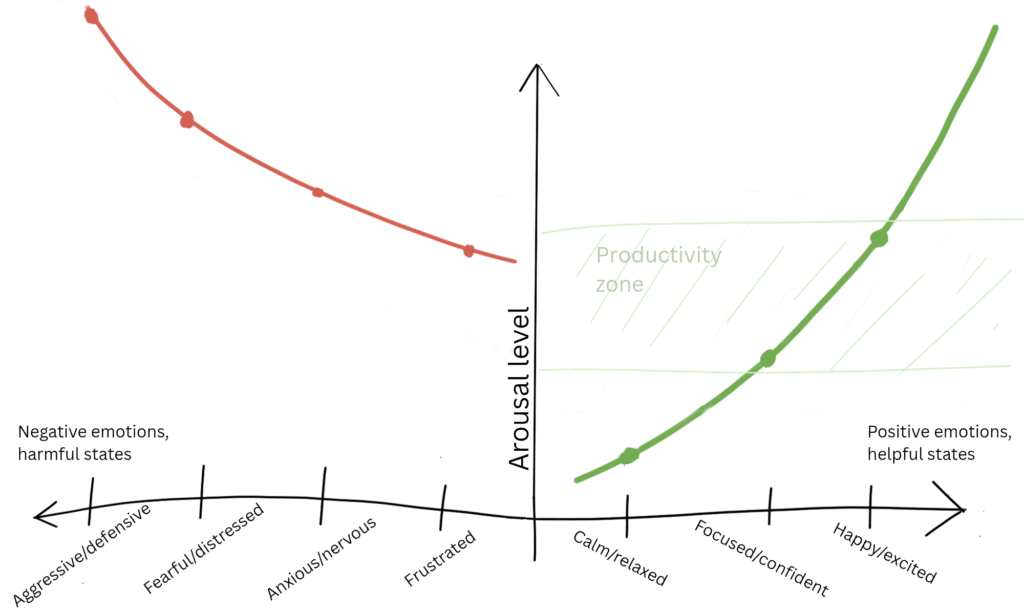

In this diagram there is same sweet spot – optimal arousal or Productivity Zone from Yerkes-Dodson law, but also it shows how different emotions with their default intensity wraps around the optimal zone. Also it’s clearly visible how different emotions has their polarity – positive or negative. Of course, in the long run working in a positive emotion side will give much better results, as constant training in frustration, anxiety or even worse – stress will backfire with dog starting to dislike this kind of activity at all.

Signs and consequences of over-excitement

Over-excitement at the trail start often shows up in a dog’s body language and ensuing search errors. Common signs include frantic behaviors: open-mouthed panting, jumping up, “crying” or whining incessantly, and pulling at the leash like a locomotive. Some highly aroused dogs might even freeze up, fixated on the scent item or the distance where the runner disappeared, momentarily unable to begin working. All of these are indicators that the dog is experiencing intense stress hormones and adrenaline. Trainers note that a dog chomping at the bit to start as soon as the harness is on may actually be over-aroused rather than optimally focused.

The consequence of starting a trail in this over-excited state is often diminished work quality. An over-aroused trailing dog might charge ahead too fast and “blow past” scent junctions, overshooting turns or important scent pools. Handlers describe these dogs as “keen but inaccurate” – they appear to be enthusiastically trailing with the lead taut, yet in reality they may have lost the trail and are merely rushing on momentum. This phenomenon, sometimes called “ghosting”, is commonly seen in high-energy breeds. Essentially, the dog’s enthusiasm has trumped its accuracy: it wants to find the person so badly that it stops carefully following the scent and begins to guess or hastily search in the wrong places. If not reined in, the dog can become desperate to find the trail layer as it realizes it’s off-scent, and the stress only gets worse and worse with each mistake. This kind of false confidence early in the trail often leads to a rapid plateau in progress – the team “hits a ceiling” where they struggle to advance in skill, because the fundamental of a controlled, focused start is missing. It can be frustrating for both dog and handler: the dog is straining with all its might but not thinking clearly, and the handler feels the tension of a search that is going away from the outset. Clearly, too much euphoria at the start line can backfire, preventing the dog from effectively using its nose.

It’s worth noting that positive excitement isn’t inherently bad – in fact, building intensity and enthusiasm is crucial for motivation and forms the foundation of many dogs’ love for mantrailing. The activity is designed to be highly rewarding (with a big food or toy payoff at the end) specifically so the dog develops a dopamine-driven “addiction” to trailing. That “feel-good” neurochemical cycle makes the dog eager to trail again and again. The key is avoiding extreme peaks of arousal. In training, instructors often say “stop on success” – meaning end the exercise while the dog is still at that happy optimal high, rather than doing “one more run” that might tip them over the edge into over-arousal. By managing arousal in this way, the dog stays motivated but mentally sharp, instead of overstressed.

Anxiety and pre-trail stress in shepherd dogs

On the flip side of excitement, anxiety or nervousness before a trail can also undermine a working dog’s performance. Handlers of Belgian Shepherds and other shepherd breeds often notice a certain anxious anticipation in their dogs right before working – for example, the dog might pace or whine in a higher-pitched tone, seemingly uncertain or edgy rather than giddy. This can happen if the dog is sensitive to the handler’s mood or if it is not fully confident in the environment. In fact, dogs have evolved to be extremely attuned to human emotions: thousands of years of domestication have given dogs an ability to interpret and even mirror our behavior and stress states. Remarkably, studies show that dogs and their owners can have synchronized stress levels over the long term, as measured by cortisol in their hair. In other words, if a handler is feeling anxious or adrenalized before a search, their dog may literally pick up on that stress and reflect it, becoming anxious as well. This emotional contagion is not just a theory – one study demonstrated that when dogs were exposed to the smell of a stressed person (an unfamiliar human), the dogs subsequently behaved more pessimistic and hesitant in a cognitive task compared to when they smelled a relaxed person. The researchers concluded that the dogs had “mirrored the negative emotional state” of the stressed individual, which then impaired their decision-making in the task. By analogy, a mantrailing dog that senses anxiety – whether from its handler or the tense atmosphere of, say, a search-and-rescue scene – might likewise become more cautious or prone to doubt itself. An anxious dog may lose focus, become restless, or struggle to obey cues, all of which can derail the critical start of a trail. Physically, high stress (distress) in dogs triggers cortisol and can even cause upset stomachs or other stress responses that obviously detract from work quality.

Especially for shepherd dogs, known for their loyalty and sensitivity, the handler’s emotional state is a significant factor. A nervous handler at the trail start – heart pounding, breathing fast – might inadvertently communicate to the dog that “something is wrong”. The shepherd could then exhibit pre-trail jitters: refusing to settle at the scent article, looking back to the handler for reassurance, or starting tentatively rather than confidently. In mantrailing, we ideally want the dog to surge forward eagerly on the correct scent. If instead the dog hesitates due to anxiety, it might miss the faint initial odor or take a few false starts, introducing confusion. Alternatively, some anxious-anticipation dogs swing the other way and explode off the line out of nerves, almost like ripping off a bandage – which circles back to the over-arousal problem. In both cases, the underlying issue is the dog’s emotional state being out of the optimal zone (too far toward the distress side).

It’s important to distinguish positive excitement vs. negative anxiety here. Trainers often refer to “eustress” – a positive form of stress that comes from excitement – versus “distress”, the negative form associated with fear or anxiety. Interestingly, the body’s physiological reaction (rising adrenaline, cortisol release) is very similar for both eustress and distress. So a Mallinois quivering with excitement to track and one quivering with anxiety might both have elevated cortisol; the difference is in the emotional context and subsequent behavior. Eustress can be harnessed for enthusiastic work, whereas distress tends to undermine performance. If a dog’s pre-trail anxiety is high, the handler should take steps to soothe and refocus the dog before letting it start. This could include short obedience routines or play to release tension, which some trainers use to “settle the brain into the task”.

For example, a simple sit-stay ritual at the trail start can help a high-anxiety, high-drive dog gather itself and approach the scent more calmly. The goal is to convert that anxiety into manageable arousal or even excitement.

Once the dog actually begins trailing, often the nervousness falls away – many anxious dogs visibly gain confidence once they are working, because they can focus on the familiar game of following a scent. In fact, mantrailing is increasingly used as an activity to help anxious or reactive dogs build confidence. It provides a constructive outlet that channels their energy into problem-solving and taps into their natural sniffing instincts. As one trainer notes, “mantrailing allows the dog to make the right choices independently, prioritizing preferred habits in the brain,” which can reduce generalized anxiety over time. The act of sniffing is inherently calming – it even lowers cortisol levels in dogs, literally helping them de-stress while they work. Thus, once an anxious shepherd gets started on a trail and realizes “I know this game!”, a lot of that worry can transform into productive drive.

Frustration: a double-edged sword

Frustration is another emotional spike that working dogs frequently experience, especially around the start of a trail or when facing difficulties on the track. Frustration in this context can arise if the dog’s goal is blocked or delayed, for instance, when the dog is held back at the start despite being eager to go, or when it loses the scent and struggles to find it again. This emotion is essentially a form of stress that often leads to agitation or impatience. Trainers sometimes intentionally use mild frustration as a motivator: by briefly blocking the dog’s access to a desired reward or prey item, they hope to increase the dog’s drive and persistence. In mantrailing, the “starting ritual” often involves letting the dog watch the runner (“trail layer”) depart and then restraining the dog for a few moments – this builds anticipation (a kind of frustration that the dog can’t immediately chase), which theoretically makes the dog explode forward with more determination once released. Indeed, learning to tolerate a bit of frustration is part of many working dogs’ training. One mantrailing instructor notes that the start-of-trail ritual “builds in frustration, and teaches the dogs to deal with the anticipation. This same frustration [in training] can enter everyday life, teaching the dog to cope with it in a non-stressful way will have a big impact”. In moderation, this frustration tolerance can make a dog more resilient and persistent – the dog learns that sticking with the task despite a brief delay or obstacle will eventually pay off.

However, frustration is very much a double-edged sword. If the frustration level spikes too high, it significantly impairs the dog’s performance, as shown by recent research. A 2025 study in search-and-rescue dogs found that after the dogs experienced a frustration scenario, their search performance measurably declined: they took significantly longer to indicate the target scent and had more “misses” (false negatives) during the search. In fact, even though the researchers only induced a mild level of frustration (comparable to common training exercises), the dogs’ efficiency suffered – even slight frustration caused slower responses and some dogs failed to alert to odors they normally would have detected. Notably, none of these dogs showed extreme reactions like aggression during the tests; they simply performed worse, suggesting that even low-grade frustration can sap a dog’s concentration and accuracy. From an operational standpoint, this is critical: a delayed or missed indication in a real search could mean a lost opportunity to find a person. The study also observed that when frustrated, dogs showed less communicative behavior towards their handlers. This makes sense – a frustrated dog might internalize its effort (“I’ll do it myself!” mindset) or become too focused on its own agitation to seek help or cues from the handler, which can further reduce team effectiveness.

Excess frustration can also boil over into outright undesirable behavior. If a dog is repeatedly prevented from doing what it expects (say, being held at the start too long, or encountering a confusing scent problem), frustration may manifest as barking, lunging, spinning, or other reactive behaviors. In training parlance, frustration outbursts are well-known. One source notes that many sports can inadvertently increase the likelihood of a dog having an outburst, listing behaviors like “barking, lunging, mouthing, even biting through sheer frustration.” In extreme cases, frustration can link with the famous “frustration-aggression hypothesis” – essentially, a blocked goal causes the dog to lash out. We rarely want a mantrailing dog to get to that stage. At the very least, a dog that’s throwing a tantrum because it’s over-frustrated is not actually scenting or thinking about the trail; it’s momentarily “lost the plot” due to emotional overload.

All this evidence suggests handlers must apply frustration carefully. Yes, a little frustration can light a fire under a dog – for example, holding back a very calm dog might pump it up to work harder. But for a lot of high-drive working dogs, especially those who are already intense, adding extra frustration at the start can be counterproductive. If you see your dog getting frantic or slipping into an unfocused state, it may be better to take a step back rather than push through. The new research cautions that training methods which deliberately induce frustration should be re-evaluated: they should only be used sparingly and with close attention to the dog’s mental state. The takeaway is to ensure the dog stays motivated but not mad with frustration. This might involve using clearer training setups where the dog can achieve success more directly (avoiding repeated false alarms that frustrate it), or interspersing challenging trails with easier ones to keep confidence high.

Positive emotions and confident work

While we often worry about too much stress or excitement, it’s equally important to recognize the power of positive emotional states in boosting a dog’s motivation and work quality. A dog that is confident, happy, and engaged will generally perform better and more reliably. In mantrailing, one huge advantage is that the activity is set up as essentially a game of hide-and-seek that the dog always wins. This does wonders for a dog’s emotional outlook. Nervous or insecure dogs often come out of their shell when they realize “Hey, I can find people and get a party every time!” The independence and problem-solving in trailing build the dog’s self-confidence in a big way. Unlike obedience drills, mantrailing lets the dog lead and make decisions, which many dogs find very empowering. Over repeated successful trails, a dog can shed anxiety and replace it with a sense of mission. Handlers of reactive or shy dogs frequently report that their dogs become more resilient and optimistic after taking up mantrailing. The previously anxious dog learns that the world (at least the trailing world) is safe and fun – there’s less time to worry about that scary stranger or loud noise when the dog’s nose is chasing a rewarding scent.

Physiologically, a dog working in a positive emotional state reaps benefits too. As mentioned, sniffing has a calming effect by releasing endorphins and reducing cortisol in the bloodstream. It’s one reason why scent work is recommended for canine enrichment – it actually makes dogs happier and more relaxed. Additionally, the dopamine release from successfully finding the “missing person” creates a pleasurable feedback loop. Dopamine is sometimes called the “reward” or “habit-forming” hormone; every time the dog trails and finds someone, it gets a hit of dopamine that says “that was great – let’s do it again!”. This not only motivates the dog to work, but it also can shift a dog’s overall emotional baseline to be more positive. A dog that regularly experiences success and reward in training will start to approach work expecting success. In behavioral science terms, this translates to an optimistic bias – the dog is more likely to interpret ambiguous clues on the trail in a positive way (“I bet this faint whiff is my person, I’ll follow it!”) rather than a pessimistic way (“This might not be right, I should stop”). A positive, optimistic trailing dog will push through challenges with tail wagging and brain engaged. Even distractions lose their power: a happy working dog often ignores irrelevant stimuli because it is so tuned in to the game. As one trainer analogized, when a dog is enthusiastically sniffing on a trail, the rest of the world fades into the background, much like how a person engrossed in a good book stops noticing the noises around them. In practical terms, a dog in a confident, upbeat state will be less likely to get derailed by distractions or obstacles. They tend to treat those hurdles as just part of the adventure, sometimes even with a tail wag – a far cry from an anxious dog who might see a distraction and interpret it as a threat or a reason to quit.

Another benefit is that a dog enjoying itself will work longer without fatigue. Stress and negative emotions are tiring – they drain a dog’s mental energy quickly. But positive engagement can be energizing. It’s why a dog can trail for a long distance if it’s having fun; the mental fatigue is held at bay by adrenaline and dopamine in a good balance. One caveat: even positive excitement still produces some cortisol (as noted earlier, the body doesn’t fully distinguish eustress from distress hormonally). So we still must allow dogs to rest and recover after intense work. However, overall a dog operating in a positive emotional range is going to have better endurance than one fighting through anxiety or over-arousal.

Finally, a positive emotional context enhances the dog–handler partnership. When both members of the team are enjoying the work, there’s a feedback loop of encouragement. Dogs are very responsive to our approval and emotions. A handler who is calmly confident and celebrates the dog’s finds will reinforce the dog’s own positive feelings. Over time this creates a strong bond of trust. The dog works not just for the reward at the end, but also for the shared joy of the mission with its handler. In essence, the best work comes when the dog is having the time of its life doing its job. So cultivating positive emotions – through play, praise, and well-designed training – is just as important as mitigating the negative spikes.

Breed related emotional temperament

Working dogs come in many breeds and personalities, and there is a broad spectrum of emotional reactivity among them. It’s important to recognize how breed tendencies and individual temperament influence the optimal emotional zone for trailing work. Trainers often informally label breeds like Malinois, German Shepherds, Dutch Shepherds, and many herding breeds as “high drive” – these dogs have intense energy and a strong desire to work, which often correlates with a higher baseline arousal level. These dogs love the game, but because they start “amped up,” it’s easy for them to tip into over-arousal if over-stimulated. If a handler fires up a high-drive dog too much with an intense start, it can “build triggers for stress in the dog even before they have started to work”. In other words, a Malinois that’s already vibrating with excitement doesn’t need additional hype – it might actually need a calming element to keep its head in the game.

It’s interesting to note that sometimes what is labeled as a breed being “high drive” is really a breed being high arousal. One trailing expert observes that dogs who “climb fast and crash hard” in mantrailing – often those who “just get the game” instantly and then yoyo between success and failure – are constantly in a high arousal state. These might be dogs like Malinois or Border Collies who are brilliant but can’t dial it down. For such dogs, more arousal is not the answer. In fact, suggestion for these dogs would be that they “need the game explained in a lower arousal way”, perhaps by cross-training in slower, methodical tracking exercises to instill patience and focus. This highlights that drive (the desire to do the task) should not be confused with arousal (the emotional intensity at a given moment). A dog can have tons of drive and love to work, but still benefit from a calm, focused mindset to execute the task correctly.

Summary

Where direct canine research is lacking, we can often draw parallels from humans and other animals to fill the gaps. The concept of performance anxiety is a familiar one in human athletes: a sprinter in the Olympic finals might be physically primed to run, but if their anxiety spikes too high, they might false start or freeze up under pressure. This is essentially the human version of what we’ve described in dogs. Just as a dog can “choke” by losing the scent due to over-arousal or fear, a human can choke in competition from nerves sabotaging concentration. Sports psychology has long applied the Yerkes-Dodson law to help athletes find their optimal arousal zone for peak performance. Trainers of detection dogs and SAR dogs are now consciously applying the same principle – recognizing that working dogs need to be in the right mental zone, not just physically fit or well-trained. The research by Bray and colleagues on calm vs excitable dogs essentially echoes what coaches observe in people: if you’re a naturally chill person, you might need some pump-up music to get “in the zone,” whereas if you’re jittery by nature, you’d benefit from deep breaths and calming routines. It’s fascinating that the same spectrum of emotional control applies across species.

Moreover, the fact that dogs mirror our emotions suggests another human lesson: a handler’s own emotional management is part of the dog’s performance. This is akin to a horseback rider; it’s well documented that a nervous rider can make a horse skittish. Riders (and dog handlers) are often advised to “take a breath, calm yourself, because your animal can feel it.” In line with this, experts recommend that handlers in high-pressure deployments practice stress-reduction techniques for themselves – such as relaxation breathing or even meditation during breaks – to avoid unintentionally transferring anxiety to their dogs. A cool, confident handler often leads to a more confident dog. It’s a team effort in managing emotions. The International Working Dog Association highlights this in advice to handlers: monitor your own stress signals and control them, because your dog is likely reading you very closely.

From other animal research, we know that emotional contagion and arousal effects are not unique to dogs. Horses, for example, have been shown to synchronize heart rates with riders and even with humans on the ground, reflecting shared stress. Similarly, studies in mice (the origin of Yerkes-Dodson in 1908) demonstrated that a medium-level electric shock best motivated mice to complete a maze, whereas too mild gave no incentive and too strong caused impairment. While we obviously don’t draw a direct line from electric shocks to dog training (!), the core idea translates: a mild challenge or stimulation enhances focus, but an overwhelming challenge triggers breakdown in performance. In dogs, that “challenge” might be the excitement of seeing a person run away (mild challenge = fun game, extreme challenge = frantic overdrive) or the stress of an environment (mild = alertness, extreme = shut down).

Even in humans, emotion and motivation are deeply linked. Psychology studies in people show that positive emotions (joy, confidence) broaden one’s ability to think creatively and solve problems, whereas negative emotions (fear, anxiety) narrow one’s focus often to a fault, or induce avoidance behavior. We see analogues in dogs: a confident trailing dog will sometimes take a clever route or persist longer (“creative” problem solving), whereas an anxious dog might either hyper-fixate on one wrong spot (“narrow focus”) or give up if it’s unsure (“avoidance”). Thus, keeping the emotional balance is part of cognitive optimization for the dog. Modern training philosophies emphasize making training like a game for exactly this reason – a dog that loves the game will learn better and perform better.

In summary, emotion spikes in working dogs can dramatically alter their motivation and the quality of their work. Whether it’s the pleasant thrill of the chase or the butterflies of anxiety, these feelings drive physiological changes that either help or hinder the task at hand. For mantrailing dogs, the start of the trail is indeed the make-or-break moment: a well-managed emotional state at the start (focused, eager but composed) is the recipe for a successful trail – the dog will dive into scenting with maximal efficiency. Conversely, if the dog begins in a frenzy or a panic, the trail can go wrong from the first turn. By understanding each dog’s emotional profile and using insights from both science and cross-species comparisons, handlers can set their dogs up for success. The goal is a dog who is motivated but mindful, driven but deliberate – in other words, a dog that loves its job and does it superbly well. As research and experience show, when the emotional equation is correct, a mantrailing dog becomes an almost unstoppable force: nose down, heart and mind fully in the game.

Leave a Reply